The Dark Labyrinth

The Work of a Deep Lead miner

Work underground in these mines was cramped, wet, dark, hot and smelly. The miners, ever fearful of drowning from sudden inflows of water or of being buried alive by the fine quicksand-like drift, worked their eight hour shifts, intensely alert to the sounds of the mine, and aware that it could be their last... but it was work and when your a miner, it's your job was to get the gold.

Hard labour

Although the surface works of a Deep Lead mine boasted all the modern advances in machine technology, the miners’ work underground remained physically intense and mentally demanding.

Up until 1902, only lanterns illuminated the blackness - the timber props, caps and laths that interlocked to form wooden enclosures were their only protection from the ‘forces of nature’ that surrounded them underground.

“Like their own shadow, the ever-present threat of an accident was with a miner” and many accidents resulting in serious injury or death were common and accepted as “the will of God” and part of the miner’s life.

Above: The Shaft Plat and the main drive. This was a busy place where all supplies and equipment for underground work descended in cages and the miners and their one tonne ore trucks manoeuvred in and out to return to the surface.

Chalks No. 1 Mine, Maryborough 1909

The volcanic flows not only buried the ancient rivers, but also the vegetation that grew along its banks. Over time the effects of volcanic heat, organic decay and water combined to produce a toxic solution and a caustic level of carbonic acid and gas that no other goldfield in Australia had ever experienced.

Carbonic acid and gas

Miners suffered daily in this hot, wet acidic ground; their calloused hands cracked and bled; boots required reinforced iron nails and plates to slow their decay and their over-pants and long ‘sou’wester’ jackets were soaked in linseed oil to keep their skin protected.

The presence of carbonic gas also brought on a condition called ‘Miners Complaint’ – the symptoms being “diminished respiratory capacity, an enlarged heart, imperfect circulation and early mental decay”.

Hundreds of miners suffered and died from breathing this ‘foul air’ “which gradually brought on the ‘dreaded malady’, for which there is no cure.”

Above: A shift at Berry Consols Extended. Photo: Creswick Museum

The Dark Labyrinth

An interwoven system of reef, trucking and intermediate drives followed the direction of the ancient riverbed and provided the underground ‘roads’ that gave access to the wash gravels.

All drives were excavated to allow water to flow back through the mine to the pump sump below the shaft. This declining gradient also assisted trucking back to the plat.

Each drive type had its own standard width and height that matched the timbers required to support its ceilings and walls.

On average a blocking drive was only 120cm high and panelling drives were even smaller.

Miners timbered the drives as they progressed and worked crouched or kneeling down as far as they could in the blocking drives where the 'payable wash' exceeded one metre in thickness. When the wash got thinner, the miner would have to lay down on his side to access the gold – this mining method was called panelling.

Pit ponies, like the one shown here, were an essential part of the workforce of the mine. They were stabled in the mine and spent their entire working life underground.

Working the 'face' in a drive.

Mateship and trust

Many of the district’s deep lead miners were the first descendants of Creswick’s gold rush pioneers and many also migrated from Cornwall bringing with them expertise they had developed from their deep tin and copper mines.

‘New hands’ gained experience by watching and working in the least dangerous parts of the mine while the ‘professional’ miner worked in areas like timbering the wash drives; a task that required working in precise unison with a mate in securing the sets of legs, caps and overhead laths.

Here their lives depended on each other’s actions and on many occasions the bravery to instinctly rescue or sadly console a mate that was trapped and being slowly buried alive by the quicksand-like drift.

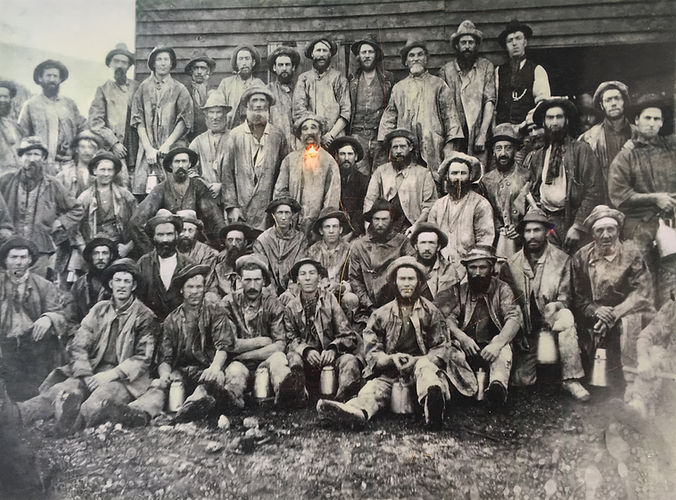

Above: A shift at Berry Consols Extended. Photo: Creswick Museum

Positive ventilation

When gold production was delayed or stopped (often for several days) by the unbearable cabonic gas, mine managers and owners were forced to look for ways to either trap the gas behind a system of air-tight doors or counteract the foul air by mechanically blowing fresh air from the surface down into the mine.

In 1896, R.B Squire, then Mine Manager at Madame Berry West, was successful in developing and implementing a system of air pipes that provided not only better working conditions for his men, but continual gold production for the owners.

Miners from West Berry Consols assemble as part of an AMA presentation to R. B. Squire in 1906. Squire was known as a competent mine manager who had great consideration for his men. Photo: Creswick Museum

Fighting for a fair go

W.G. Spence was one of the founders of Creswick’s Amalgamated Miners Association (AMA) when at a meeting in Broomfield 1878, a mass protest was organised against several mine owners at Spring Hill who attempted to reduce contract rate of pay for reef driving.

The AMA became the foundation for Australia’s trade unionism and its strong membership contributions to accident and death payments were by far greater than that paid by the mining companies.